South Asian Migrants

In Greece

understanding migration trajectories

Beginning from the 1990s, Greek economy has benefitted significantly from cheap and flexible migrant labour from Eastern European countries such as Albania, Bulgaria and Romania, and more recently from the South Asian countries of Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan. These migrants take seasonal or all-year low-paying and flexible jobs in immigrant-niche sectors such as agriculture, construction, processing plants, tourism, and other service sectors. They are paid low wages that range from €22 – 25 per 8 – 10 hours of work with no breaks. This wage is much below the minimum wages in Greece. Their undocumented status lends to lack of protections from wage theft, less than minimum wages, lack of health insurance, or other worker safety protections.

South Asian migrants, almost all men, are drawn to Greece as it is the first EU country overland offering a gateway into the men’s preferred northern European countries of Germany or England. As of 2020, the number of South Asian migrants working in Greece is estimated to be around 150,000 - 200,000 with a majority of them with undocumented status or those who overstay despite the rejection of their asylum claim. They are typically in their 20s; young and unmarried or with spouses back home; minimally educated, low-skilled, or unskilled; and from rural lower or lower-middle class backgrounds. With the exception of Sikhs among Indian migrants, the rest are Muslims.

South Asian men, very much like other migrant workers, find temporary and seasonal work due to local labour shortage in certain sectors that have been vacated by the native Greeks. The reasons include a shift to labour-intensive cash crop farming, an aging rural population, and the reluctance of young rural Greeks to take up low paying, physically exerting agricultural work. Migrant labour is attributed to boosting productivity and expansion at a crucial period when Greek farmers shifted to high value but cash crops. A significant number are employed in the urban informal economy such as in construction, automotive services (car repairs and petrol stations), and in shops such as communication centers, and grocery shops which cater to migrant communities.

Their migration occurs within a larger political economy of neoliberalism, agrarian crisis, privatization of social services such as healthcare and education, political and civil unrest. The men poverty, lack of employment opportunities and mounting debts as motivators to seek opportunities for a better life for themselves and their families beyond the borders of their countries of origin. Additionally, the presence of regularized Bangladeshi, Indian, and Pakistani migrants is an incentive for men from their kin or villages to migrate there.

Where do South Asian migrants work in Greece

Each year, thousands of young South Asian men from Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan come to Greece as undocumented migrants. The reasons for their migration are diverse yet often overlapping: chain family migration, romantic aspirations to go “overseas,” household risk diversification strategy, or breadwinner masculinity affirming strategies. Their migration occurs within a larger political economy of neoliberalism, agrarian crisis, privatization of social services such as healthcare and education, political and civil unrest, and violence against ethnic or religious minorities. Many of these men leave families behind, and dream of bringing their spouses and children to Greece once they are settled.

To give a context, nearly 200,000 undocumented men from Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan are estimated to be in Greece. They are typically young; poorly educated, low-skilled, and from rural lower-class families. They work in low-paying and precarized immigrant niche sectors of agriculture and the informal urban economy. With the exception of Sikh migrants from India, the Bangladeshi and Pakistani men are Muslims.

How do South Asian migrants LIVE in Greece

Housing

The living conditions of migrant workers in Greece are varied. Most migrants employed in agriculture live in informal houses constructed on employers’ land and in close proximity to the farms.

For example, in Manolada, workers live in housing camps constructed out of materials such as bamboo, recycled plastic materials, cardboards, and reeds. These plastic shacks are called Baranga, a Bangladeshi colloquial term derived from a Greek word, paranga, which translates as “a shack.” They are forced to rent unused farmland from the farmers or locals and build these highly inflammable makeshift shacks. With a rent of US$33-38 per baranga, a person renting their land stands to earn US$500-550 per month from just one baranga alone during the growing season that runs from mid-December until mid-May.

-

Clusters of 10-17 barangas each house a minimum of 200-350 workers. In the summer, the temperature inside reaches 50C and in winter, it is below freezing. For drinking water, they purchase packs of bottled water, a necessity that eats into their meagre monthly wage. Outdoor toilets consist of holes dug in the ground covered with wood slats and plastic sheets wrapped around four poles to provide privacy. “Showers” are open-air platforms.

-

The inadequate sanitation, waste-disposal facilities and drainage create ripe conditions for workers falling sick to diarrhoea, fever, asthma, respiratory problems, and skin rashes. A Bangladeshi farmhand sums up the sentiments of other workers in saying, “Neither the Greek state nor the afentiko (boss) care about our lives or health. Only our cheap labour matters.”

-

In Megara and Thiva, the makeshift dormitories are colloquially called “Deras” or “Stores” respectively in by the men. These consist of sheds or warehouses, where farm supplies, pesticides, seeds, and implements are usually stored, and where, by the crude plyboard partitioning of walls, and the provision of run-down fridges, gas stoves, and collapsible cots, undocumented labourers too get similarly stored. This figurative transformation of the men into objects, on the same scale of use value as pesticides, weedicides, or rototillers, reveals the utter disposability of these agrarian workers within the capitalist accumulative process. Each Dera in Megara houses a minimum of 6-10 men whereas in the Thiva region, cavernous warehouses or stores provide shelter to as many as 30-40 men each. Almost all of these dormitories are mono-ethnic in composition.

-

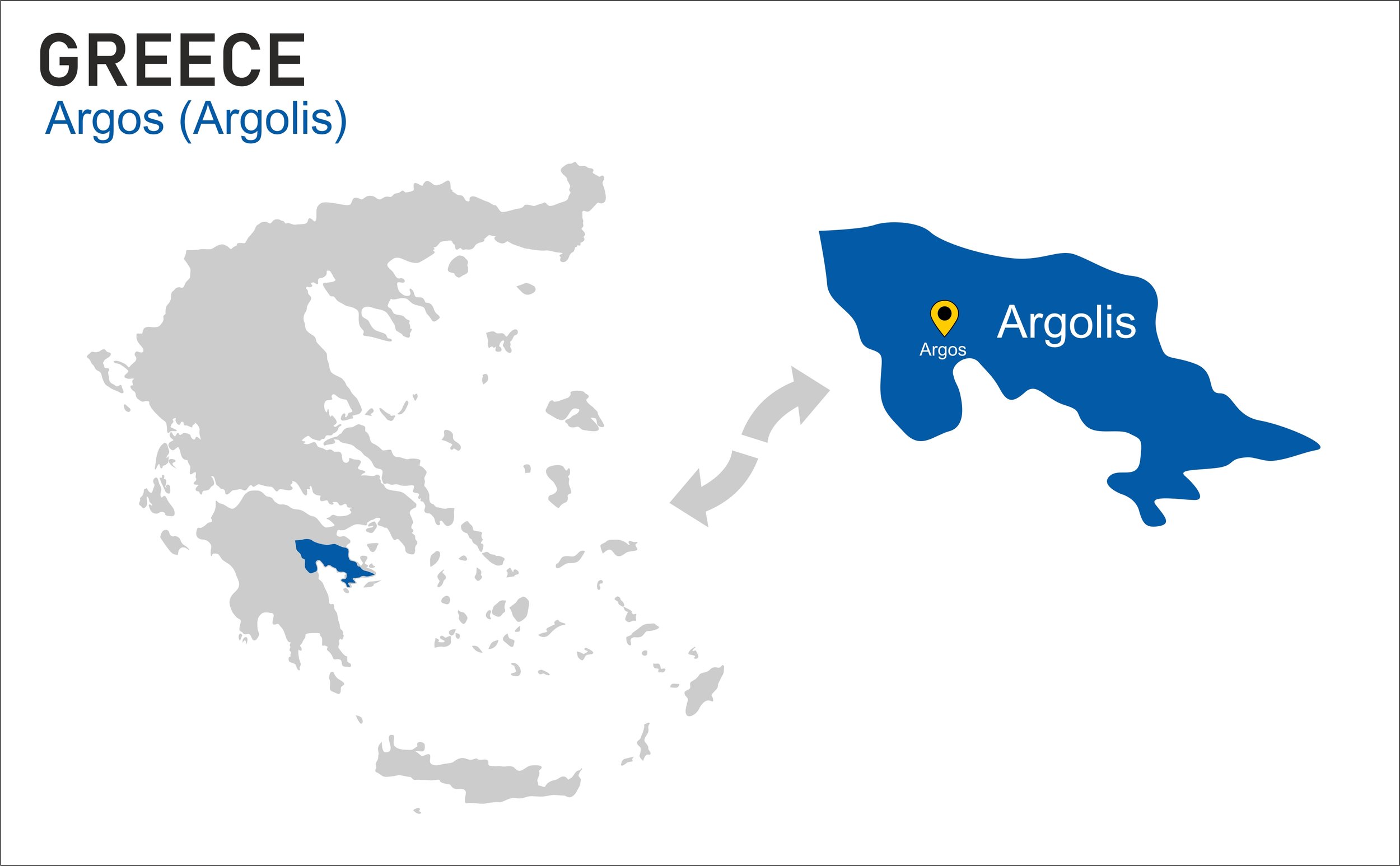

Similarly, in Argos, small one or two room single-storied dwellings called spiti are located in villages next to orange orchards where workers are forced into sharing bunkbeds. The spitia (plural) are seasonally occupied by the migrant men. Once again, many of these spitia lack basic amenities such as attached toilets. However, these do have running water and electricity, a small comfort in the midst of other hardships they have to endure. In all these housing situations, it is up to the largesse of the farmers who own the housings to either charge a monthly rent or as a Pakistani farmhand who worked in Thiva stated, “allow us to live freely on the farm. It allows the farmers to obtain free 24/7 security for their expensive farm equipment, and water pumps.”